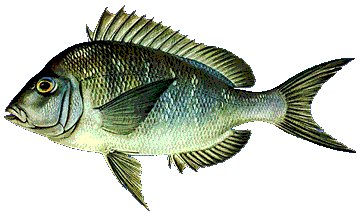

Porgy (Scup)

Stentotomus chrysops

Profile by Stacey Reap

Range:

Scup have been found along the Atlantic coast from the Bay of Fundy and Sable Island Bank, Canada, to as far south as Florida; however, the greatest concentrations can be found from Massachusetts to North Carolina. Depending upon the season, they can be found from coastal waters and estuaries out to depths of approximately 650 ft. along the outer continental shelf. A separate population of scup referred to as the "southern porgy" or S. aculeatus, is referenced in several South Atlantic Bight studies; however, there is no official differentiation made between the two populations by the American Fisheries Society.

Size:

Scup of both sexes are sexually mature by age 3, at an average length of 8.3 in. Historically, scup have been reported at lengths of 18 in. and up to 4 lbs and 20 years of age, but the current Middle Atlantic Bight population is composed mostly of younger fish, few older than 7 and larger than 13 in.

Food & Feeding:

Juvenile scup feed on small organisms, such as polychaete worms, amphipods, small crustaceans, and mollusks, as well as fish eggs and larvae. While copepods and mysids are more important to early juveniles, the diet of larger juveniles is more dependent upon bivalve mollusks, such as razor clams and blue mussels. The scup diet typically consists of a mix of reef and sandy-bottom prey, with adult fish having broad culinary tastes ranging from small crustacea, squid and fish to polychaetes, mollusks, vegetable detritus, hydroids, and sand dollars. With two rows of strong molars in their jaws, scup are able to crush hard-shelled prey.

Migration:

Scup in the Middle Atlantic Bight demonstrate a pronounced seasonal migration from summer inshore grounds to offshore wintering areas along the outer continental shelf. They also show movement from north to south, although few fish tagged in the New England/New York vicinity in the summer are caught south of Cape Hatteras. As coastal water temperatures drop below 7.5°C (45°F) in September, scup begin migrating in schools of similarly sized fish. Schools from the Mid-Atlantic arrive offshore in December, wintering in deep water as far south as North Carolina, their distribution dependant upon water temperature. Bottom water with a temperature of 7.3°C (45°F) is their lower preferred limit, with the location of this favored isotherm influenced by the Gulf Stream. The migratory patterns of the scup population south of Cape Hatteras are unclear, although the fish may move offshore during the coldest weather.

Spawning:

Scup travel inshore to spawn once a year when the water warms past 10°C (50°F), which occurs May through June in New York and New Jersey bays. Spawning continues in July along coastal Rhode Island and extends through August, when water temperatures are approximately 24°C (75°F). Spawning fish are found in southern Massachusetts shoal waters until late June, after which they move to deeper waters. Eggs are fertilized externally, with scup between 17.5 cm (6.9 in.) and 23 cm (9 in.) averaging about 7,000 eggs per female.

Habitat:

Although they are occasionally seen at the surface, scup are bottom-dwelling fish. With a diverse benthic diet and using schooling as a defense strategy, scup do not require structure for habitat, but they can benefit from it. As a result, they are commonly found associated with hard-substrate environments, such as mussel beds, artificial reefs, rocky outcroppings, and wrecks, but are also found in areas with soft, sandy bottom. Once scup travel offshore to winter in deeper waters, their specific habitat preferences become unclear. Although they remain demersal, they have been found dwelling in a variety of offshore habitats.

Recreational and Commercial Importance:

Scup are important to both recreational and commercial fishermen in New Jersey, but, as a result of overfishing and habitat loss, scup catches have become less abundant. The 1998 total combined New Jersey commercial and recreational landings of just over 5 million pounds were the lowest in the 1981-1999 time frame, with 1999 showing only a slight increase to 5.2 million pounds. Commercial landings in 1997 were the lowest since 1930, at only 7% of the 1960 peak landings of 48.5 million pounds. Recreational catches have also declined. In the early 1950s, scup comprised 33 to 49 percent of the state's party boat catch; the total recreational catch amounted to 2 million pounds. In contrast, in 2000, New Jersey anglers kept only 335,000 scup, probably less than 200,000 pounds. The principal commercial fishing gear for scup is the otter trawl.

The fishery is now managed under the Summer Flounder, Scup and Black Sea Bass Fishery Management Plan, which establishes annual gear regulations and quotas for commercial operations, as well as recreational size and possession limits. Recreational fishermen accounted for 20-50% of the total annual coast-wide catch from 1985-1999, taking 1.8 million pounds of scup in 1999. In 2001, the New Jersey recreational regulations allowed for a possession limit of 50 fish over 9 in., with a season running July 4 through Dec. 31. Under these regulations, the scup catch increased in 2001 to 585,000 fish.

Recreational anglers use small hooks on top and bottom rigs to catch scup. The most commonly used baits are squid and clam. Party boats account for the majority of the recreational scup catch.

At night they adopt a darker pattern, with vertical bars, usually more pronounced than this.

Good News for Anglers:

Management strategies, including recreational size limits and commercial quotas, are paying off. Over the next few years, more and bigger scup will appear on NJ reefs.

References:

Range, Steimle, et al. (1997), Morse (1978); size, Steimle, et al. (1997), Terceiro (2001); feeding, Steimle et al. (1997), Morse (1978), Murdy, et al. (1997); migration, habitat and spawning, Steimle, et al. (1997); fishery, Terceiro (2001), Beal et al. (2000); recreational catches, Younger and Zamos (1955), Figley et al. (2001).

This article first appeared in New Jersey Reef News - 2002 edition

Sheepshead (right) is similar, but much larger, with bold vertical stripes.