Aquarium Guide - Health

The most common and treatable fish disease in both freshwater and saltwater is Ich ( or Ick. ) However, although they have similar life cycles and symptoms, the freshwater and saltwater varieties are actually quite different, and caused by entirely different organisms. In both cases, the organism is a parasite, which has three major life stages:

- a free-swimming stage where it is looking for a host

- a feeding stage, where it is embedded in the host's tissues

- a reproductive stage, during which it forms a cyst and drops off the host

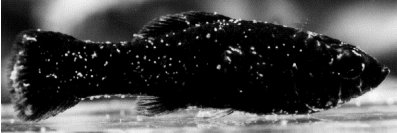

During the feeding stage, the parasite causes small white dots to appear all over the fish. Although they appear first on the fins, by the time this is apparent the parasites have already infested the gills. With a heavy enough infestation, the fish will suffer respiratory and osmotic distress from the tissue damage, eventually resulting in death.

The ich parasites occur naturally in all waters, and it is likely that all fishes carry a low-level infection. Lethal occurrences of ich in the wild are rare, because of the low probability of any single parasite finding a suitable host during its brief swimming stage. However, in a closed system such as an aquarium, the natural balance between parasite and host that occurs in the wild is tipped heavily in the parasite's favor. Most of the time, in the confines of even a large lightly-stocked aquarium, many parasites will find hosts. After just a few generations, the parasite population explodes and overwhelms the fish.

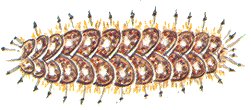

Trophont (phase I) |

Tomont (phase II) |

Theront (phase III) |

|

Single-celled adult parasite feeding on fish. This is typically when you'll know that your fish is infected with Ich, as you will see 'grains of salt'. |

The trophont enlarges, breaks out of the cyst and falls to the tank bottom. The trophont becomes encapsulated at the tank bottom (a tomont), where it begins to divide internally into hundreds of single-celled parasites. |

Theronts ( swarmers) are free-swimming microscopic parasites, which hatch from tomonts in search of a fish host. One tomont may hatch as many as one thousand theronts. |

|

Note: |

Note: |

Note: |

Only the free-swimming stage of the ich parasite is treatable by usual means. In freshwater, this is a simple matter of dosing with any of the commonly available cures, over a period of several days to several weeks. Most of these involve some kind of blue-green dye, which kills the swimming parasites. The parasites that are already on the fishes are not treatable, but will fall off in time. Likewise, the reproductive cysts are not treatable, until the swimmers hatch out. The life cycle of the parasite can be accelerated by raising the water temperature, although many cold-water fishes cannot tolerate this. Curing freshwater ich is relatively straightforward and easy.

Saltwater or marine ich is a different matter entirely. This is caused by either of two different organisms, both of which are much more resistant to treatment than the freshwater ich parasite. Low-level infections may be retarded by dye or copper treatments, but in truth, neither of these are very effective in curing the disease and are totally ineffective against a major breakout. An added drawback is that many of the standard marine ich treatments, ineffective though they may be, are deadly to invertebrates such as anemones, and many of them seem to be equally lethal to the fish they are supposed to cure! Copper is the same active ingredient in bottom paint, and in high enough concentrations is lethal to all living things. Even a trace of copper in the water can cause echinoderms ( starfish, urchins, etc ) to simply disintegrate.

Fortunately, most of the local temperate fishes are relatively immune to the disease, far more so than tropical fishes. The best way to avoid marine ich is to avoid its worst carrier, the Spotfin Butterflyfish. Do not keep these fishes - almost nothing can withstand the onslaught of disease that they will inevitably bring into your aquarium. Likewise, do not add any store-bought specimens to a tank - these are often loaded with tropical diseases which will run wild among your native fishes. Another fish that is especially susceptible to Ich is the Naked Goby.

I have never successfully treated a case of what I would call "Butterflyfish Disease". In the end, I have had more than one tank become a total loss, not in the least due to the harmful effects of the "treatments" on the entire system. Most of these so-called medications will upset the biological balance of your aquarium so badly that it will turn into a fetid stinking mess with nothing left alive.

The fastest and easiest way to clean out marine ich and recover a tank like this is to drain it and refill with cool tap water. Don't worry about the chlorine. Make sure to continue running the filters, so that the entire system gets a good freshwater flush. The marine ich parasites cannot survive freshwater immersion ( nor can they survive drying ), and all stages of the parasite will be killed. In freshwater, they swell up and literally explode. After a day, drain and refill the tank with saltwater. The beneficial nitrifying bacteria in the gravel and the filter will largely survive this treatment, and the tank will be usable again in several days. Stock it lightly at first, as you would a new tank.

In general, the aquarium trade makes a lot of money selling "cures", most of which do not work, and many of which are more harmful than helpful. While in theory many of these should work, in practice, the end result of most chemical treatments is usually the same - a dead tank. The truth is, apart from ich, you have very little chance of even correctly diagnosing a fish disease, and chances are that by the time you have noticed it, it is already too late. Throwing chemicals and antibiotics at an unknown malady is more likely to do harm than good. This is especially true of antibiotics. A far better cure for most minor diseases, including low-level outbreaks of marine ich, is to improve the water quality and reduce the parasite population through water changes.

A non-chemical treatment that is effective on marine ich and other parasites is UV ( ultraviolet light ) sterilization, which will destroy the free-swimming parasites before they can get to the fish. This is not 100% effective but may reduce the parasite population to a low enough level that the more resistant fishes recover on their own. Weaker fishes should be released, they will have a better chance of recovering in the wild, and in any case, they will no longer be able to reinfect the others.

In the end, prevention is far better than cure. The best prevention for all types of fish diseases is to maintain healthy water conditions. Don't overcrowd, perform regular water changes, and avoid species that are known to be disease-prone.