Ships & Barges

Old Ships Make New Homes For Fish

Old vessels make excellent artificial reefs. They provide high profile structure for pelagic fish, low profile structure for demersal fish, as well as surface area for the attachment of mussels, barnacles, tubeworms, and other food organisms. Shipwrecks have been the basis for the state's bottom fisheries which feature sea bass, tautog, ling, cod, and pollock. and for recreational scuba diving activities. The New Jersey coast has a large number of shipwrecks, estimates range from 500 to 3,000. These wrecks are the result of 200 years of maritime disasters and enemy submarine operations during World Wars I and II.

Despite the variety of shipwrecks available to anglers and divers, these aging structures are deteriorating, breaking up, and sanding over. The Artificial Reef Program is providing a new supply of shipwrecks, within easy range of the state's ocean inlets, that will become increasingly more important in the future as the old wrecks disintegrate.

Only steel-hulled vessels are acceptable for sinking on artificial reefs. Wooden vessels are not dense enough to stay in place on the seafloor and are quickly torn apart and scattered by storms. Floating on the surface, wooden debris poses a serious threat to navigation; on the bottom, uncharted debris tears up nets and dredges of commercial fishermen. Even thick fiberglass hulls, which do not deteriorate in saltwater, are broken into pieces by storm surges on the bottom.

Sinking a ship on an artificial reef is not simply a matter of towing it offshore and blowing a hole in it. There are many laborious and expensive steps that must be taken before a derelict vessel becomes a new home for fish.

First, the vessel must be cleaned of pollutants arid pass a U.S. Coast Guard pollution inspection. Cleaning usually entails removing all loose floatable debris, such as wood, paper, containers, compressed air cylinders, and mattresses, and draining and flushing of engines (if they are not removed), fuel tanks, cargo tanks, hydraulic lines, and bilges. After cleaning, the next step is to vent all internal watertight compartments and bulkheads to ensure that the vessel floods without trapping air and sinks properly.

On some vessels, parts of the superstructure have to be cut down so that once sunk on a reef, they do not protrude above the navigation clearance requirements imposed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Most of New Jersey's artificial reefs have minimum clearance requirements of at least 50 feet over the highest point of any reef structure.

Another step in preparing a ship is to remove the propellers or secure the prop shafts to make sure the shaft packings do not leak during towing. An anchor or heavy piece of steel or concrete and a length of chain, cable, or nylon line at least twice as long as the water depth at the reef site are needed to hold the vessel in position while it sinks. After the slow tow from port to the appropriate reef site, the vessel is anchored in position, making certain that it is within the reef site boundaries and at the correct depth.

Sinking can be accomplished with explosives or by opening engine room seacocks. In the case of the 165-foot cargo ship Pauline Marie, a licensed contractor set off three small charges along the keel, opening up 2-foot diameter holes and sinking the vessel in 10 minutes. The 265-foot tanker Morania Abaco was sunk by a Navy Explosives Ordinance Disposal team in one hour. Two other tankers, the 247-foot sister ships, Francis S. Bushey and A.H. Dumont, as well as several tugs and barges, were sunk by cutting 2-foot square holes through the hull above the waterline and then opening the seacocks. Sinking in this manner usually takes one to three hours.

Whichever method is used, the goal is to do as little structural damage to the vessel as possible. This will allow the new wreck to survive many more storms and increase its effective life on the ocean bottom. By leaving the ship intact, its immediate fish productivity is reduced. The flat surfaces of the hull do not offer many hiding places for fish and lobster. But as deterioration proceeds and the wreck begins to slowly break apart, its productivity for marine life and anglers will increase. Thus, a new shipwreck is like a time capsule with its best results delayed, but prolonged over a 50- to 100-year time span.

From A Guide to Fishing & Diving New Jersey's Artificial Reefs - New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, 1989

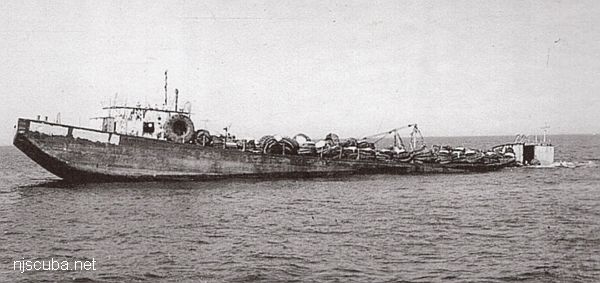

Excess Barge Sunk as Artificial Reef

Source: David Kelby

On June 17 the second of five excess barges was towed from the SSES dock on its way to a July 16 sinking in the Atlantic Ocean off the coast of Point Pleasant, New Jersey.

The YON-97, YO-230, YW-127, YOGN-8, and YOG-58 were once used by SSES as mobile fuel oil systems to meet the requirements of test site operations. With the installation of a new fuel farm, these barges were no longer needed. Under PMS 308's SINKEX Program, the barges were excessed, and all will eventually meet the same underwater fate as the YON-97 ( sunk in June 1997 ) and YW-127. This barge was turned over to the New Jersey Fish and Game Commission for use as an artificial reef. New Jersey's shore experiences a lot of erosion. Artificial reefs help preserve the shores, as well as provide a place for sea life to escape the tidal action and look for food.

Before being turned over to the New Jersey Fish and Game Commission, the YW-127 was made environmentally friendly. During the first quarter of FY-98, the barge went through a cleanup process to ensure no PCB contamination or oily waste and sludge remained. The cleanup involved a total rip out of the flanges, the gaskets around the ductwork and hatchways, the cable, and all the wiring. The tanks and bilges were also cleaned.

The detailed disposal process is led by Code 363, the Philadelphia branch of the Facilities and Model Fabrication Department. Assisting with the June 17 tow, were Robert Cairns (91412), Edward Featherer (91414), George Huber (91412), Ronald Marino (914), Andrew Pasinski, (91412) Michael Sweeney (91412), David Tryon (91415), and James Winter (91412), who all served as line handlers.

"Once we transfer ownership of the barges to New Jersey through GSA, the state handles the actual sinking of the vessels, " said David Kelby (363), who managed the cleanup and turnover of the excess barges. The sinking is sponsored by private individuals and corporations. No tax dollars are used. For more information contact: Mary Zoccola at ZoccolaMA@nswccd.navy.mil or (301) 227-1165.

from Navy records