Lavallette Wreck - Argyle?

- Type:

- shipwreck, sailing ship, Canada

- Specs:

- ( 107 x 24 ft ) 408 tons

6 crew & passengers - Sunk:

- Sunday, January 28, 1855

ran aground in storm - 5-10 casualties - Depth:

- 12 feet

Launched at Eel Brook on November 11th, 1848 the Argyle was described as a "beautiful modeled barque, a first-class vessel built of the best material, copper fastened and is ironed kneed throughout." ( Knees were angular shaped pieces of iron or timber which were used to fasten the horizontal deck beams to the vertical frames - iron was stronger and took up less space in the hold and, therefore, meant a better-built vessel. )

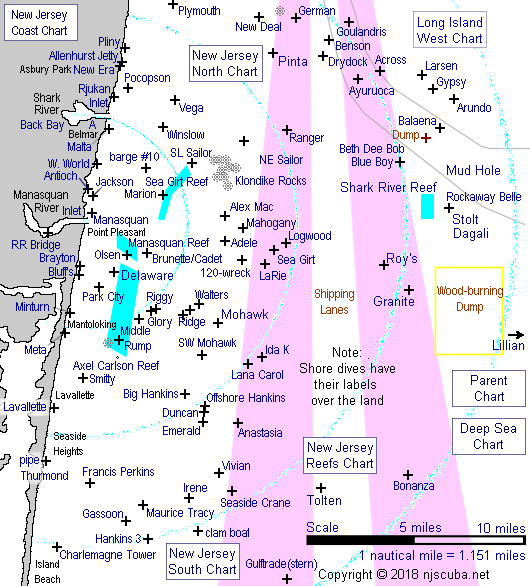

The "Lavallette Wreck" illustrates the difficulty in identifying old shipwrecks. It is described as a low wooden wreck, 100 yards off the beach in 12 feet of water, over a mud bottom. It is almost certainly the remains of an eighteenth or nineteenth-century sailing ship.

Many vessels are listed in historical records as lost at "Squan", or "Squam", "Squam Beach", or any number of variations of what we now call Manasquan. Modern-day Manasquan is a small town just to the north of the Manasquan inlet; it has approximately one mile of beach.

In 1685, the entire area from Manasquan south was named Squan Beach. This includes the towns of Manasquan, Point Pleasant, Bayhead, Lavallette, and Seaside Heights, among others, as well as Island Beach State Park. One old account gives the former location of Cranberry Inlet ( closed in 1815, now Seaside Heights ) as "Squan Beach, " and as late as 1878, Lavallette itself was referred to as "Squan Beach." Therefore, a wreck reported at "Squam Beach" could actually be anywhere between Sea Girt and Barnegat inlet!

In early times, these desolate barrier islands were practically uninhabited, with few roads, landmarks, or witnesses to events. Eventually, lifesaving stations were erected, but even these were miles apart - Manasquan, Bay Head, Mantoloking, Chadwick Beach, and Toms River. Thus, old accounts are likely to be extremely imprecise, if not outright wrong. Add to that primitive communications, sloppy reporting, lost records, shifting sands, and years of pounding by the ocean surf, and it is not hard to understand why so many shipwrecks have never even been found, let alone identified.

Several possible identities for the Lavallette wreck are listed below - ships that are known to have been lost at "Squam", but have never been positively identified as any particular wreck site.

Yarmouth Herald 1 February 1855 p2:

LOSS OF BARQUE ARYGLE, OF THIS PORT - LOSS OF LIFE !

The following telegraphic dispatch has been received by E.W.B. Moody, Esq.:

New York, Jany 30.

E.W.B. Moody, Esq., Yarmouth.

Argyle totally lost Sunday night, Squam Beach - one man saved - five left on wreck.

The Argyle was owned by E.W.B. Moody, Esq. - and commanded by Capt. James Burton and was from Glasgow bound to New York with a cargo of iron. Vessel and freight insured at the Yarmouth Office to the extent of L2000.

Record of the Shipping of Yarmouth, N.S. pp230-233:

Distressing Shipwreck!

NARRATIVE OF the WRECK OF the BARQUE ARGYLE, CAPTAIN JAMES BURTON, AND LOSS OF ALL HANDS EXCEPT ONE.

The Barque "Argyle, " of Yarmouth, 408 tons, Captain James Burton, sailed from Glasgow, Scotland, for New York on Christmas Day, 1854, with a cargo of iron, and went ashore on Sunday night, 28th January 1855, at Squam Beach, about twenty-nine miles below Sandy Hook, New York.

The shock was sudden - the waves immediately began to break over the vessel with terrific fury, and those on board, eleven in number, were compelled to seek safety in the rigging. They could see the shore indistinctly, about three hundred yards off, but as they could not venture on deck for the purpose of forming a raft, they were compelled to remain in the rigging, hoping that the long-wished-for morning might bring them some assistance. There was one passenger, a Scotchman, who, with one of the hands, a boy about 16 years old, was swept overboard with the same wave which carried away the boats. The others lashed themselves to the masts, with the exception of one seaman, the only person of the whole crew who was saved. This man held on by his hands, in the foretop; and after an exposure of fourteen hours on the wreck succeeded in reaching the land by swimming.

At length, after six terrible hours of agony and suffering, during which they were drenched with spray and exposed to the piercing winter wind, the day began to break, and they saw a vessel about half a mile from them. They made signals and were answered, but whatever hope they might have entertained when they first observed her, vanished, as she proceeded on her course without taking further notice of them. It was, in fact, impossible to give them any assistance, situated as they were in the midst of breakers. No attempt, however, was made, and they now watched the shore with the most intense anxiety, as their last hope. They were soon gratified with the sight of a man; and in less than half, an hour after there were some twenty or thirty on the beach. They had been observed by some person connected with the lighthouse, who obtained all the assistance he could. At this time there were nine men on the wreck, and it was believed that if a rope communication could be made with it and the shore, that they could be saved. The mortar was accordingly brought out, and a ball, with a rope attached, fired over the vessel. One of the crew succeeded in seizing it, and was proceeding to make it fast to one of the masts, when, from some cause, it gave way, and all subsequent attempts to establish a communication, failed. It is said by some that this failure was attributable to some defect in the mortar or the other apparatus. As it was impossible to save them by this means, one of the persons on the shore volunteered to go off to the wreck in a boat if any others would accompany him; but there were none daring enough to venture their lives. All but this brave fellow considered it impossible to get through the surf, which was thrown to the height of ten or twelve feet on the beach, and he was accordingly forced to remain a passive spectator of the terrible scene before him.

About twelve o'clock one of the sailors fell from his place on the foretop, and, striking on the deck, was killed. He was afterward found on the beach, with the front part of his skull broken in. The man who was saved was observed several times in the act of undressing and dressing again but did not venture to leave the vessel till about two o'clock, after fourteen hours' exposure. Then, without any article of dress upon him except a pair of cotton drawers, he leaped into the sea, and made for the beach, which he succeeded in reaching after a struggle of twenty minutes with the waves, during, which he frequently disappeared from the sight of those on shore. As he was completely exhausted, however, he would doubtless have been swept away by the receding waters had not one of the spectators gone into the surf, with a rope fastened round his waist, and helped him out. He was taken immediately to the house of Mrs. Betsy Chapman, about half a mile distant where he received proper care and attention. An hour or so after, the Captain, evidently emboldened by the success that attended the first attempt, was seen making preparations to leave the wreck. Deliberately taking off his coat and boots, he descended the rigging and running along the side of the vessel, jumped into the sea as far as he was able. As he appeared to be a powerful man, it was thought that he would succeed in reaching the shore safely; and this thought was confirmed, as they saw him about halfway from the vessel struggling with unabated vigor. Their hopes were soon dispelled, however, as they saw him overwhelmed by a huge wave, after which he was seen no more till his body was thrown up by the sea upon the beach amid the fragments of the wreck.

The vessel now began to break up, and the poor sufferers, exhausted by cold and long exposure, fell off one by one until only five were left. There they were, within three hundred yards of the shore; but those who saw them dare not venture to their assistance, as the waves continued to run high, and it was almost impossible for any boat to clear the surf. Before night closed on the fearful scene, not a living soul was left on the wreck, and the timbers that were occasionally thrown on the shore showed that it would soon go to pieces. Before the next morning, not a vestige remained of the vessel, except a portion of her bows, which, it is supposed, was attached by a chain to the anchor which lay beneath.

All the bodies were found before Tuesday night, some of them eleven miles from the scene of the wreck. Four were taken to Squam, where they were interred in the Methodist graveyard, with appropriate religious services. Three were buried at Point Pleasant, which is about ten miles from the village of Squam.

The name of the seaman saved was Paul DeCosta. He shipped at Glasgow, and belonged to Canso, Nova Scotia. The four bodies which came ashore at Squam were recognized by him as Mr. Jones (mate); and seamen called John (a Frenchman); Augustus (a Frenchman); and Henry Prock, colored man, supposed to be of Indian extraction.

The bodies of the Captain and 2nd Mate were buried at Point Pleasant., Three more bodies came ashore at Shark River, about ten miles from the wreck. The captain's trunk was washed ashore and taken charge of by Mr. Morriss of Long Beach.

The "Argyle" was owned by E. W. B. and J. W. Moody. [newspaper says J.W. and J.B. Moody] of Yarmouth, N.S. Capt Burton leaves a wife and four children (residing in Carleton) to mourn their sad bereavement. - St. John Courier.

Item above includes a few additions which were in the original article from the Yarmouth Herald of 15 February 1855.

historical accounts & images courtesy of Eric Ruff /

Yarmouth County Museum, Yarmouth, Nova Scotia

Another ship Argyle is listed as lost "3 miles south of Squan Beach" in March 1852. Listed as a Swedish bark, this is thought to be a different vessel, but may in fact be a transcription error in the records.

Questions or Inquiries?

Just want to say Hello? Sign the .